The Pandemic Recession, part 5: Post-Pandemic

Economies are fast making a full recovery at the aggregate level: with GDP rapidly back to or even above pre-pandemic levels, and employment recovering fast. But consumption patterns look very different: spending is up massively on sport & recreation goods, on cars, houses and home improvements, and on tech and online shopping. Spending remains lower on travel, food and accommodation. Are these changes in consumption permanent, or will they soon pass?

A personal favorite anecdote of consumption changes during the pandemic lockdowns involves eggs. When people go to the supermarket they prefer to buy free-range eggs, or at least barn eggs. In contrast when they go to restaurants or get take-away the eggs being served are typically barn eggs or caged eggs. In short, when you buy eggs you care more about the chickens, when the restaurant buys eggs for you they care more about the price. Lockdown meant no more restaurants and people were instead buying all their eggs from supermarkets. The result was a sudden shift in demand away from barn and cage eggs towards barn and free-range eggs (there is a longer-term trend in the same direction for both supermarkets and restaurants).

Related to both the shifting consumption patterns and also to shifting employment conditions there has been a spike in inflation. Historical pandemics have not been associated with inflation (quick general caution, most work on what happens after historical pandemics identifies them by their death tolls which are typically much larger than the present Covid-19 pandemic). This suggest that the inflation spike as of mid-2021 will be transitory, although obviously this will also depend on how monetary authorities react.

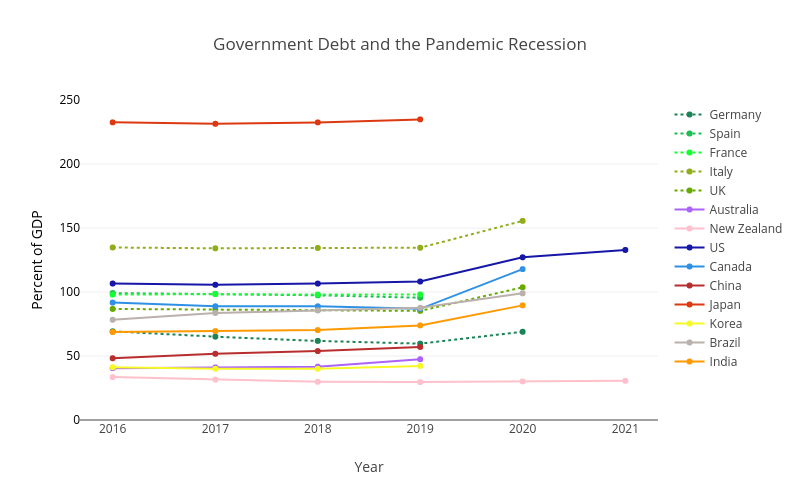

One important future challenge is that once the pandemic recessions are over countries will find themselves with higher levels of Government debt. Figure 1 shows how Government debt (as a percentage of GDP) increased substantially during 2020 for many countries. In 2020 UK Government debt increased by 18%-of-GDP, the US by 19%, India by 16%, Canada by 31%, and Italy by 21%.

This increased Government debt has likely reduced the fiscal space of many countries for reacting to future recessions and crises. It will also accelerate difficult decisions that many countries face around ageing which will drive increased future pension obligations (more retirees) while taxes to pay for them will not grow nearly as much (less working age people as fraction of population). Reduced pensions, increased taxes, working longer? None of the solutions will be easy. Reducing Government debt is likely to have important economic impacts over the coming decade: Fiscal austerity?, Financial Repression?, Inflation?, Government Debt Crises? Loosely related, in the 1980/90s there was substantial forgiveness of debt owed by low-income countries that had been lent to them by high-income countries during the previous decades on grounds they could not repay; think Live 8 concerts. Something similar may be replaying right now with China as lender via Belt-and-Road Initiative (e.g., Sri Lanka). Note that heavily-indebted poor countries unable to repay was not the aim of the earlier lending, nor of China’s current lending, but it was the result.

Let’s wrap this up with a few final thoughts. Much of this discussion and related evidence depends on the nature of the Covid-19 pandemic. It disproportionately kills the elderly (65+ years old) who are mostly non-working. It is not deadly enough to younger people to kill a large fraction of the working population. By contrast in 1918 the Spanish flu mostly killed people aged 20-30 years old. Substantial amounts of work can be done online without personal contact (in high income countries); roughly 25% of work in high-income countries versus 14% in low-income countries. (As high as 35% in US & UK, and 40% in Canada.) We also saw the importance of Governments ability to transfer targeted aid to people directly and digitally. Or in developing countries, lack of ability. A different pandemic (more infections, or more deadly, or kills young rather than old) may require substantially different responses. Let’s finish on the optimistic thought that as more work continues to shift to being digital the trade-offs in any future pandemic may involve better options?

Extra: References and resources (get a copy of the graphs :)

If you are lost here is a link to the first post in this series on the Pandemic Recession.